Is inflation (also) a self-fulfilling prophecy?

Thoughts on the narrative dimensions of inflation

Erick Behar-Villegas

5/3/202315 min read

Image by Henry Rodríguez (2022)

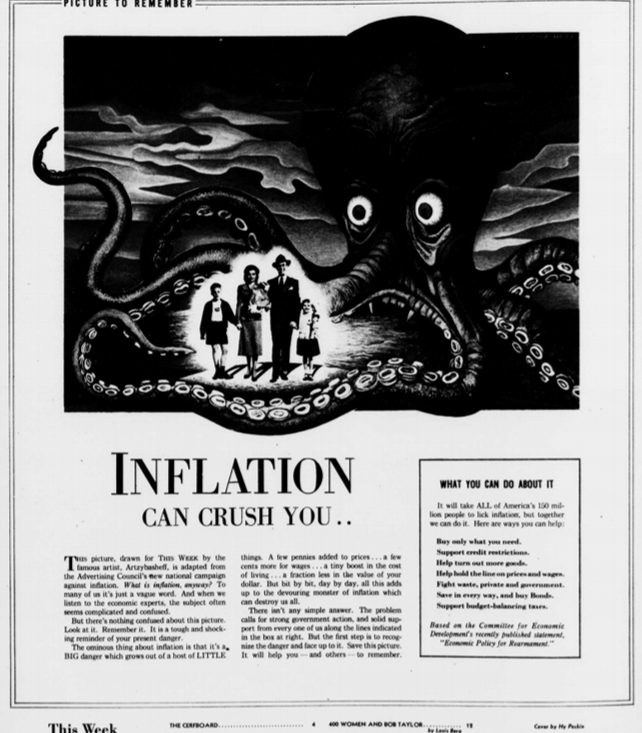

Have you felt frustrated when looking at those price tags? At a year’s difference, commuters in Brazil have been paying 158% more for gas, consumers in Germany around 48% plus for butter and there is even a meme making the rounds with singer 50 cent adjusting himself to 85 cents. This reality rekindles the inflation octopus that This Week magazine featured in the 1950s; it haunted families and companies, with good reason. Now, some years after Central Banks industriously loaded up those balance sheets and unleashed the Kraken of the printing press, the United States brought the euphemistic Inflation Reduction Act to the table, a Law that should tackle climate change, budget deficits and high drug prices while partly boosting government spending and tax enforcement. With the uncertainty that not only Putin & Co. are fueling, winter is still coming, and inflation will continue to accompany our conversations. Before we explore it further and begin asking questions about self-fulfilling prophecies, let me tell you the story of aunt Bertha.

Source: ProQuest - The Week (1951)

The year is 1923. As her niece Dorothea would say, aunt Bertha was a wonderful person who loved to help others. But they wouldn’t always correspond with good deeds. Bertha would take strolls through the overcast Berlin during those times that Americans remember as the roaring 20s. And roar the did. Just not for Bertha. Some years before, while the Weimar Republic was shining on paper, she had used her share of the family inheritance for the needs of her sister Emma. Lucky for her, the sister was responsible enough and paid her back quickly. Unfortunately, though, this happened in the obscure year of German hyperinflation. When she got the money handed over, Bertha ran with it to her brother Wilhelm’s shop, but it was too late. All she could afford with the former equivalence of a house, yes, a house, was a salty silvery herring [1].

I began writing this essay in Berlin and hoped to finish it in Istanbul, one the modern inflation capitals of the world. Turkey is bedridden with an official inflation rate above 76%, but I trust Professor Steve Hanke’s index more, which points to more than 122%. I have gathered stories on inflation in Turkey, which follow the same pattern of psychological pressure and frustration stemming from the evaporation of people’s hard earned savings. The most powerful statement I heard is “we ask for the inflation rate before we even say good morning now”, and the other one that left me thinking, from a nice barista in the Beşiktaş district was: “now I have to put up more hours of work, here or somewhere else, to buy the same stuff”.

Inflation, currently en vogue, hurts many, especially the poorest. At a first glance, we do not need an essay to remind us of that reality. A glimpse into the past paints the recurring picture. In a study carried out fifty years ago regarding the realities of families battling inflation, more than 30% of respondents admitted having problems in their marriages, while more than 25% of them underwent mental health issues given the financial pressures they faced [2]. The picture is clear. Yet we could use an essay to shed light on a curious ingredient in the recipe of soaring prices: narratives and self-fulfilling prophecies, which naturally relate to psychology. In order to do this, I will first explore some of the causes of inflation that the economic literature has pinpointed, before swimming into the wild waters of self-fulfilling prophecies and inflation.

Part I: Where does inflation come from? A recap on some reasons

You may have read Friedman’s famous proposition, “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon”, better yet, “it’s made in Washington”. Beyond the opinion that Friedman may deserve from each one of us, he made a very important point in one of his famous speeches. You can fuel inflation by printing more money or by boosting government expenditures. This gives us food for thought, but it is not the whole story. To get there, let us inventory some of the typically cited reasons for soaring prices, which don’t always apply given the diversity of contexts. If you are versed in the matter, you can skip the “reasons” and jump to Part 2.

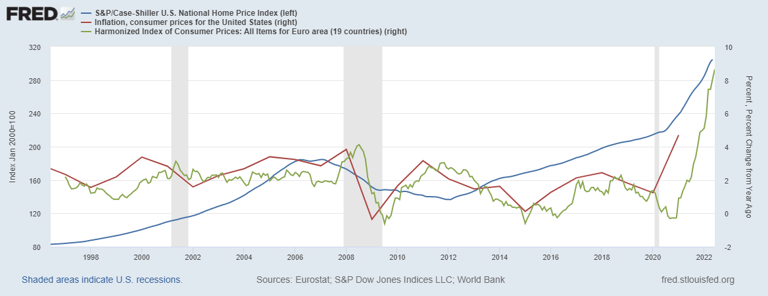

Reason nr. 1: increase of the money supply

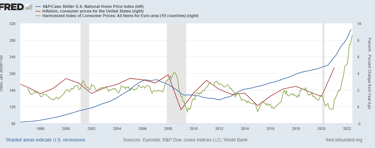

When an economy sees its money supply (usually the M2 you see in graphs) grow beyond output (GDP), it is creating money at a margin that the production process no longer supports. If you produce apples and agree to print one bill per apple, even two or three, the day in which you decide to print 100 bills per apple will only serve as an illusion of wealth and make those apples expensive if production stays the same. Of course, history has shown that (more) money oils the economy and that the availability of credit allows for investment projects and even the realization of John Doe’s wildest dream of owning a house (or a luxury car). The following image shows you how the money supply has grown in the United States, along with the Consumer Price Index, which economists use as a base to measure inflation.

Image source: FRED

Without getting into the math and bringing back the delicacy of Jean Bodin’s 16th century cogitation, the quantity theory of money (QTM) asserted that the price level increases in proportion to the amount of money in circulation (Money in circulation x velocity of money = overall price level x real value of expenditures). If you want to understand part of this principle and have some fun, watch this episode of Duck Tales.

Yet things are not as straightforward as they seem. As J. Williams explained in a speech at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco some years ago, when the monetary base doubled between 2009 and 2012, inflation still oscillated around 2%. This example can hardly be generalized in countries that do not have a vehicle currency like the dollar, the euro or the pound sterling, as they are in demand beyond punctual trade or financial market transactions (e.g. buying bonds).

Reason nr. 2: government spending

This is one essential point in Friedman’s many disagreements with Keynesian thought. We know that the view of Keynes in his General Theory (1936) followed the idea that the economy could be stimulated via consumption, investment and government spending, pulling a country out of a recession and thus avoiding the hardship of massive unemployment. The problem, however, is that money is not necessarily neutral and that an economy can fall into fiscal-policy driven inflation. If the government spends beyond its own returns, for example, with creative mechanisms such as bond purchasing programs, ornamented in fancy acronyms like TARP (Troubled Assets Relief Program) or if it increases the size of the public sector via debt, there will be more money out there, and possibly higher prices.

Reason nr. 3: Sticky prices

When economists speak of sticky prices, it means that they are not easy to adjust downwards, or officially “slow to change”. For example, your employer cannot surprise you tomorrow with a 50% off your salary, unless the situation is extreme and a legal mechanism allows something similar (employee furloughs, Kurzarbeit in Germany, etc). Depending on the legal system, she will feel a generous set of consequences if she does it arbitrarily. If prices do not adjust downwards and households have seen their incomes dwindle when they pay much more for a certain category of goods, sticky prices in other categories will be proportionally more cumbersome. You can look at the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s “Sticky Price Consumer Price Index” here. Since August of 2021, the SP-CPI has been on the rise, though not at the same speed of the CPI.

Reason nr 4: the zero-bound

This one is very close to reason nr. 1. Not too long ago, many marveled about taking up credit for almost 0% interest. Remember that the price of money is the interest rate itself. The cheaper money is, the lower the interest rates will be, whether we are talking about European standard facilities or the federal funds rate of the United States. Go back to the subprime crisis of 2008-2009, right at the time when I was majoring in economics and my professor felt bewildered by “people making 2000 dollars and having six credit cards and a spending capacity of 20.000 dollars and beyond!”. It is true that the prosperity of many Western countries has been at least partly based on cheap credit and good institutions [3], but every extreme has its peril. It is no wonder that as inflation expectations soar and interest rates go up, banks have to tighten their credit conditions.

Reason nr. 5: external shocks

Milton Friedman disagreed about the oil price shock as a reason for inflation. Amid the oil crisis of the 70s, he said that inflation was not the responsibility of some Sheik, but we can wonder about the sad mix of decisions in the current energy crises and question Friedman’s view. Is Putin, taken together with the permissive German government’s attitude towards cheap Russian gas and the anti-nuclear narrative, not partly responsible for the energy price surge? Inflation was already increasing before the invasion of Ukraine, but uncertainty and expectations mix into a cocktail that we cannot ignore. I don’t think that the Italian activists who glued their hands to Botticelli’s Primavera to criticize cheap energy understand that a sustainable energy revolution needs a financially sustainable transition, a thought that they probably don’t share with the other artists that glued their hands to Van Gogh’s Peach Trees in Blossom in London with “Just Stop Oil” shirts. The good news is that these activists, unlike the first ones, only put their hands on the frame of the painting.

Reason nr. 6: price controls

This is one good example of good intentions gone wrong. High prices? No problem, cap them, things will relax, and we’ll all be on our way. Except that in this world, that friendly recipe does not work. As Shuettinger and Butler wrote in their 1970s masterpiece, after 40 centuries of price controls, the mechanism seems doomed to fail to curb inflation. In spite of some exceptions that may work temporarily in pharma given different health urgencies and benefits for patients, this is a dangerous recipe. A curious story can illustrate this.

In the late 70s, Egypt was known for heavily subsidizing food and building massive deficits that were not reflected in higher productivity. Price controls ended up in shortages of fruits and vegetables, but the strangest thing happened with the effects of bread subsidies. It turns out that bread was so cheap it was being used as cattle fodder, and it was too late to do away with the subsidy, unless the government wanted a price explosion. Shuettinger and Butler rest their case with a curious statement from an Egyptian government official “when we realized that the fancy cake sold at the Hilton Hotel to rich tourists was made with subsidized flour, subsidized sugar and subsidized shortening, we started to review the thing” [4]. Take a more modern example, the Berlin rent cap, introduced by the local government in 2020. While the prices did go down initially, there was a 52% cut in housing supply [5], making it hard, if not impossible, for newcomers to find a place to live. This is followed by further transaction costs for those who have to change places every month until they get something after even several years. The bitter cherry on the cake is that –after their odyssey– newcomers will have to pay 396% more for gas compared to last year prices as they settle in.

Reason nr. 7: price pass-throughs

Incentives matter and so do expectations. If you have a small business that employs several collaborators who get paid the minimum wage, and the government throws down a 50% increase on you, you have several options: you can absorb the shock if you have good profit margins, you can absorb it with terrible profit margins and eventually go bust, or you pass on the increase, partly or fully, to your customers, hoping that the competition does not force you into market exit eventually. The literature on minimum wage increases has been flowing into an interesting consensus: mildly raising it does not lead to unemployment [6], but hiking it dramatically can be associated with more unemployment and price pass-throughs. One study published in 2019 shows how in Hungary, about three quarters of the cost of a major increase in the minimum wage was funneled to consumers [7].

Part II: On self-fulfilling prophecies and narratives

Think about how discrimination works. John thinks Matt is evil. John gives him no opportunities, hits him, isolates him and vilifies him. Matt eventually reacts and fights back, making John convince himself of his originally false claims.

The famous Thomas theorem of sociology goes something like this: “if we define situations as real, they will be real in their consequences” [8]. Twenty years after William Isaac Thomas and Dorothy Swaine Thomas published this maxim in The Child in America (1928), the American sociologist Robert Merton coined the term “self-fulfilling prophecies”, referring to false definitions of a situation that brings about new behavior and makes that false definition come true [9]. Said differently in the context of economics, mere expectations can make things happen. In the 1980s, L. Jussim gave self-fulfilling prophecies three stages: you develop expectations, act accordingly and those that are influenced by your acts react in “expectancy confirming ways”.

As I write this essay, announcements about expected inflation in the UK rounding 15-18% are heaping up. Meanwhile, the German press is speaking about price-wage spirals (prices go up, you ask for more money, firms hike their prices, you ask for more money, and so on), and inflation is beating Kim Kardashian(!) on Google Trends, as you can see further below. For David Wilcox, director of US Economic Research at Bloomberg, inflation is “to an important degree” a self-fulfilling prophecy. In his CNN Business column, he writes that “if consumers believe inflation will ease, they’ll be less militant about demanding large pay increases (…) and employers will be more resistant to granting them” [10]. After looking into the University of Michigan’s Consumer Sentiment Survey, he seems a bit more optimistic, but does not rule out the “dire scenario”. I can imagine that he does not want Daniel Defoe’s words to come true regarding the British financial markets of the 18th century: we have “bubbled a nation!”.

Claiming that inflation is a self-fulfilling prophecy is more complex than claiming that it is a narrative. The latter can be seen as the way we tell stories, and, here is the interesting issue, it can push stories into reality. As an abstract idea, it seems convincing, but actually measuring to what extent inflation works as a narrative, let alone as a self-fulfilling prophecy, is a tremendously hard task. Yet there are interesting approaches out there.

Is there a narrative-dimension to inflation?

After Robert Shiller published Narrative Economics in 2019, linking narratives to economics seemed to flow into a clearer consensus, even if the measurement issue still operates to a certain extent as the elephant in the room. Consider one example from the world of policy. For Kleinheyers and Mayer [12], market actors transfer information via narratives. As an example, they use the famous speech of Mario Draghi om January of 2021, when he said that the European Central Bank would do “whatever it takes” to protect the euro. One day after the speech, the 10-year yield of Italian government bonds plummeted (this is a good sign for a country. The contrary speaks for more uncertainty). So stories seem to help, but how do you isolate the cause and avoid being, in Taleb’s words, fooled by randomness? Here are some hints from recent research.

First, the media seems to be a good predictor of inflation and inflation expectations. The latter are built especially via our shopping experience, knowledge of monetary policy and prior experiences. Second, shaping the expectations of those who set prices can have a direct effect on price changes, but there is an issue: the expectations of households and firms are rather different. On top of this, information seems to blur away after 6 months, making expectations a heterogeneous phenomenon [13]. In other words, information nurtures expectations via narrative-building, a process that can seep through to price-setters who adapt their expectations to the available information they have. Consider this example provided by Anna Hirteinstein in the Wall Street Journal. Given the expectations of rising energy prices in 2021, fund managers bought up energy futures as a hedge against inflation, fueling it in the process [14]. The risk here, as Gary Duncan mentioned in 2008, is that inflation becomes “embedded in the system” while high interest rates slow down the economy.

In his book, Shiller addresses the famous “profiteering” narrative that flourished in the United States and Germany after World War I. In a nutshell, businesspeople were seen as greedy and corrupt, willing to extract money from war heroes and the general population through price increases. People were furious, demanded higher taxes for firms and even prison, until the government effectively imposed the excess profits tax of 60%. As Shiller narrates, people spoke of profit-hogs and eventually contributed with this behavior to the “consumer-boycott-induced depression” of 1920-1921 [15]. In the end, the narrative fulfilled itself and multiplied the effects against some scapegoats and possibly some bearers of true guilt.

Coming back to our present, we would be unwise to simply blame companies as initiators of inflation. In this text, together with you, we have already reviewed more structural causes, but this doesn’t rule out that some companies do see some temptation and possibly trick customers without losing face and admitting to price increases. Let me use several pieces of chicken to give you an example of what economists calls shrinkflation. A giant German retailer, which operates as trendsetter in all things ‘price & packaging tricks’, used to sell chicken breast filets in 600g packs. Now, these look tremendously similar, except for the weight, which is now 400g. And it’s not only that discounter. Others follow suit, even big brands such as Haribo, as the German newspaper Tagesspiegel reported.

Consumers who like to register prices and compare them eventually see that they are paying similar nominal prices for the same box, which now contains a 4, not a 6, and of course, less chicken or gummy bears. The massive literature on economic psychology that one now links to behavioral economics has a lot to say about our bounded rationality. No, we do not systematically realize these little changes in product packaging. As R. Thaler, one of the renowned economists of that stream of thought says, we are humans, not econs. D. Ariely, another behavioral economist, summarizes it very well: we are predictably irrational, and the problem with this is that it may cater to interests that are not necessarily our own, making decisions against our own well-being without noticing it. As a honey enthusiast, I see this time and again. Companies that include honey in crackers smartly say that they come “with honey”, but then you look at the dire reality and honey amounts to 1-2% and the rest is not history, it’s high fructose corn syrup, or something of the like. Still, we may fall for it and convince ourselves that we are eating healthy crackers.

An interesting comparison regards Disney World. Until the 80s, rents, wages, gas and tickets to Disney World seemed to rise at the same speed, until Disney tickets started skyrocketing and more than tripled the increase of wages in the United States. You can have a look at a wonderful data visualization on the matter here. This begs the question whether embedded expectations do not serve as a temptation to increase prices even further of companies that retain much market power thanks to their brand positioning. As we remember the story of aunt Berta in the 1920s, it is important that we keep our eyes open for shrinkflation and keep a sane amount of skepticism at stories that become, narratives and evolve into very expensive self-fulfilling prophecies.

Notes

[1] Adapted from the German Zeitzeugen Repository. DHM. Available under https://www.dhm.de/lemo/zeitzeugen/dorothea-guenther-die-inflation-1923.html

[2] Cf. Caplovitz, D. (1981). Making Ends Meet: How Families Cope with Inflation and Recession. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. Retrieved from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/000271628145600108

[3] Bernstein, W. (2021). The Delusions of Crowds. Grove Press.

[4] Shuettinger, R.L. & Butler, E.F. (1978). Forty Centuries of Wage and Price Controls: How Not to

Fight Inflation. The Heritage Foundation, p.100.

[5] Sagner, P. & Voigtländer, M. (2022). Supply side effects of the Berlin rent freeze. International Journal of Housing Policy. Special Issue, Forthcoming. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2022.2059844 Accessed: 22.08.2022

[6] See, for example, Jardim, E., Long, M. C., Plotnick, R., Van Inwegen, E., Vigdor, J., & Wething, H. (2022). Minimum-wage increases and low-wage employment: Evidence from Seattle. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 14(2), 263-314; Cribb, J., Giupponi, G., Joyce, R., Lindner, A., Waters, T., Wernham, T., & Xu, X. (2021). The distributional and employment impacts of nationwide minimum wage changes (No. W21/48). IFS Working Paper; Clemens, J., & Strain, M. R. (2021). The heterogeneous effects of large and small minimum wage changes: Evidence over the short and medium run using a pre-analysis plan (No. w29264). National Bureau of Economic Research; Bossler, M., & Schank, T. (2020). Wage inequality in Germany after the minimum wage introduction. Labor and Socio-Economic Research Center Discussion Paper Series, Nr. 117.

[7] Harasztosi, P., & Lindner, A. (2019). Who Pays for the Minimum Wage? American Economic Review, 109 (8), 2693–2727.

[8] The original formulation appeared in The Child in America in 1928: “if men define situations as real, they are real in their consequences" (p.572) in the Alfred A. Knopf edition.

[9] Paraphrased from Merton’s definition in “The Self-Fulfilling Prophecy”. The Antioch Review, 8 (2), 193-210.

[10] Wilcox, D. (2022, July 27). Opinion: The toughest part of the Fed's job may already be done. CNN Business: Opinion. URL: https://edition.cnn.com/2022/07/27/perspectives/fed-interest-rates-inflation-consumer-expectations/index.html

[11] see Bernstein (2021, p.86)

[12] Kleinheyers, M. & Mayer, T. (2020). Discovering Markets. The Quarterly. Journal of Austrian Economics, 23 (1), 3 -32.

[13] See Coibion, O., Gorodnichenko, Y., Kumar, S. & Pedemonte, M. (2020). Inflation expectations as a policy tool? Journal of International Economics, 124 (1) and Larsen, V.H., Thorsrud, L.A., Zhulanova, J. (2021). News-driven inflation expectations and information rigidities. Journal of Monetary Economics, 117 (1).

[14] Hirtenstein, A. (2021, October 21). Investors Buy Oil on Inflation Fears, Pushing Prices Even Higher. URL: https://www.wsj.com/articles/investors-buy-oil-on-inflation-fears-pushing-prices-even-higher-11635672603

[15] See Shiller, R. (2019). Narrative Economics. Princeton University Press. Chapter 17.

Contact

behar@berlin-international.de

Address

Berlin, Bogotá, Monterrey or Madrid