The birth of the realfluencer

How an entrepreneur wants to change the influencer marketing industry, using the wonders of cognitive psychology.

NARRATIVESPSYCHOLOGY

Erick Behar-Villegas

12/30/20238 min read

Sextus Turannius was a funny fellow. He lived in Rome at the time of Jules Caesar. In spite of the good health that accompanied him to the post of Procurator at age 90, he decided it could change. He fell into his own mental disgrace when the famous Caesar fired him. As Seneca says, he became a corpse; he couldn’t endure rejection, especially not from the big boss of Rome. Luckily for him, against all odds, he got reinstated. Miraculously, his health and good mood came back. He just needed the approval of Caesar to feel good about himself [1]. We could speculate about the degree of influence a person like Jules Caesar had on the minds of others in Rome back then, but we can all agree that, especially after crossing the Rubicon, whatever he thought or did actually mattered to most people.

Whether we like it or not, we tend to be influenced by others. As Laurence Scott wrote in 2019 for the New Yorker [2], influence has a rather elusive quality; we don’t know what’s behind the scenes sometimes. It’s the opinion of someone who can affect our destiny, maybe it’s simply the unhealthy cereal that you bought because of the persuasive ad, or its the nice design of a box that tempted your senses. Perhaps it’s the whole storytelling and myth-building that’s behind the city you ended up moving to. It’s not a secret. There is a ton of science, especially cognitive psychology, even a wide array of speculation and many narratives out there on the topic of influence, especially now that social networks have pushed forward the world of influencer marketing. But I think that –as normal people– we can skim that very dense world to get some value and actually gain something from the world of influence. Before we get to the concept of the realfluencer and its creator, let us set the stage by talking about the psychology of influence.

Influence and Persuasion: our daily lives

Maybe you remember the efforts you made, light or not, to fit into some group when you were a kid. Imitating the behavior of others appears as something normal in our lives. Back in in the 19th century, French sociologist Gabriel Tarde exemplified his study of imitation by making us think of how the son (partly) mirrors his father’s behavior. Those closest to him could exert a very important influence, even if the son or the daughter deviated powerfully later on. When we mix this with some curious findings in medicine, it dawns on us just how much others can affect our behavior.

In 1948, the famous Framingham study started gathering information on blood pressure, cholesterol, body weight, among others, with a cohort of 5209 participants. Over the years, researchers also asked themselves whether someone’s surroundings in terms of personal networks would be associated to changes in these variables. Two of the researchers involved in this project, Christakis & Fowler [3], asked whether obesity was a multicentric epidemic, meaning it could spread from person to person. Using Bayesian probability, they found that the chance of being obese is higher the closer you are to an obese person (45%).This led to the idea of three levels of personal networks, i.e. friends of my friends’ friends. The closer someone is, the more prone we are to be influenced.

And it is not only about body weight and blood pressure. Our emotions can easily be targeted as well. To get an idea, consider Facebook’s infamous experiment that took place in 2012. The researchers manipulated the amount of positive and negative posts on a sample of ca. 689.000, hence the word “massive” in their article [4]. They found that increasing positive posts led users to having a higher likelihood of posting something positive, and the same goes for negative posts and negative reactions. Recall that all of this happens within a digital personal network, which Facebook has sought to make more “familiar” in the last years. Curiously, researchers also found that when both negative and positive posts were reduced on their news feed, users tended to be less expressive, reducing the amount of words in their posts. Without a doubt, emotions matter.

The concept of influence has been present in social psychology for a long time. Robert Cialdini published his bestseller Influence: the psychology of persuasion in the 1980s, bringing in some principles about how we persuade others, especially in matters related to consumption decisions. Think about it with the following story.

Tom went into a store and received a box of chocolates at the entrance. Staying true to his own promises of healthy food, he packed the chocolates away and decided to give them to some of the kids at the school he works for, but they gave him a good feeling about the place. When he reached the computer section at the store, he marveled at the new monstrous gamer laptop. “There’s only one left, buddy”, said the sales guy smiling, both hands in his pocket, not losing sight of the laptop. “really?”, Tom answered while also staring at the computer, touching the color-lit keyboard. “Yes, I wouldn’t lie to you, especially not for that laptop. Do you want to come to the storage and see the empty shelves?”. “No, it’s all right”. Tom took out his phone and there he was, Dr. Tech, talking about how that laptop was unlike anything he had ever seen before. And those contours, that design, let alone the speed! He remembered his other buddies playing with that same computer two nights before. There was nothing comparable, and Tom had saved a long time for something better. Tom sighed and thought for a moment. He thanked the sales guy and left the store in a jiffy. Outside, amid the heat of the tarmac, he turned around, looked at the computer store and said, “what the heck. If it’s still there after thirty minutes, I’ll take it!”.

The story involves Cialdini’s six principles of persuasion, which include: reciprocation (we tend to give back to others), commitment & consistency (we commit to ideas as a base to making decisions), scarcity (we ascribe more value to a product that is not available, or simply put: less is more), authority (we tend to accept more from those we believe in), liking (it’s easier to agree if we like each other) and social proof (the herd helps us feel better about our decisions when they decide the same thing).

Tom’s case may be different to our daily transactions, as not all principles devised by Cialdini appear at the same time. The interesting matter is that they extend beyond consumption to other scenes of our daily lives. For Cialdini, our use of mental shortcuts (heuristics) is crucial when it comes to making decisions. This is an idea that you might have read about in other popular works such as Thinking Fast and Slow, Made to Stick, etc. If you are a psychologist, this is something you’ve surely heard of from the very first semester at college in your social psychology classes.

In more recent work, Cialdini talks about putting some mystery in order to engage and motivate others [5], which in turn reflects the power of myth-creation that has been used since time immemorial. This goes in line with his argument on “pre-suasion”, which refers to optimizing persuasion by changing your target audience’s state of mind, not just by convincing them of accepting your views. The idea is to seek agreement from your audience before sending them a message, so it’s easier to digest. For example, when you want to sell the idea of healthy food, you might begin a general conversation about the risks that unhealthy foods pose.

The curious world of Influencer Marketing and an entrepreneur’s dream

Part of Cialdini’s message has to do with using science for the purpose of better business, which –I hope– should always involve ethical considerations. Jump now to the curious world of influencer marketing, where behavior and visibility intertwine to affect even how people feel. Science has a lot to say there as well. In a Forbes article from 2019, Bradley Hoos summarized some of these aspects. For example, pressure to behave like others may be interpreted by our brain as a potential punishment if we break a social norm. Think about dressing like a cucumber for your next day at work (not Halloween). Think about what would go through your mind as your colleagues observe you in awe (and full admiration). Would you do it? Even better, what are you waiting for? Feels strange, right? Another aspect that Hoos highlights is that influencers are able to shape seemingly personal connections, leading to more trust. This is surely funneled by looking into their everyday lives, etc. [6] And there is much more: the power of aspirational ideas, the desire to learn, the desire to build one’s own identity, etc, but the key issue for me here is that we might just be breaking the three step rule of networks that stems from the Framingham study. Maybe we perceive that they are much closer to us and hence adapt our behavior in that which the famous Spanish writer, Leopoldo Alas, called “noble emulation”.

The realfluencer: a different view of the industry

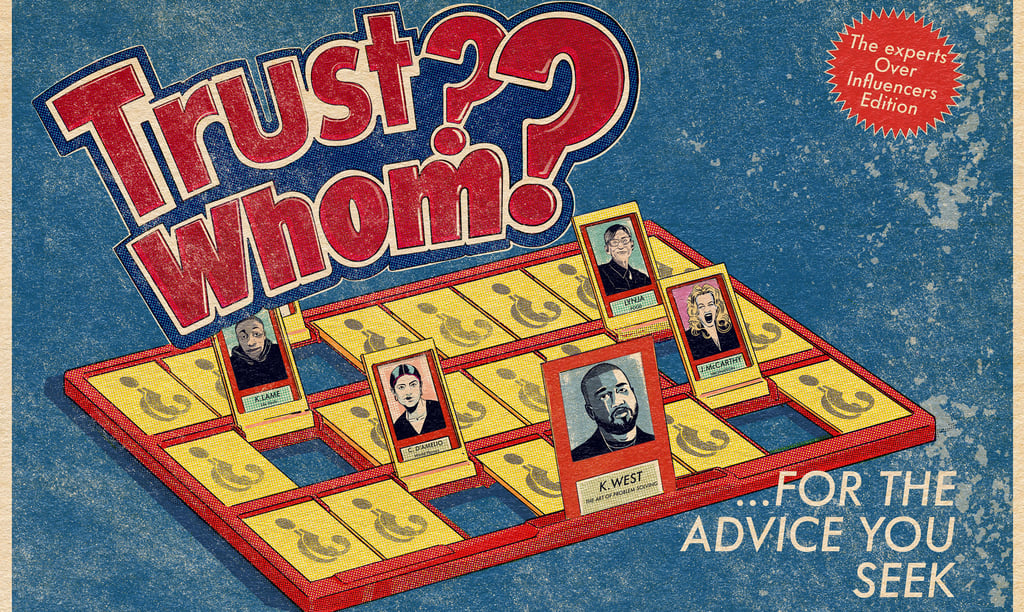

Enter Max Beck, the German entrepreneur who just put something very convincing on the table. For him, the difference between the typical celebrity-influencer and the real value-adding person of influence is enormous. One is visible and need not have something real to offer, though a lot of cash to absorb, whereas the second one, the realfluencer, is someone who cuts to the chase and actually helps a person or a company get somewhere with real expertise and knowledge. According to Max, every realfluencer is an influencer, but not every influencer is a realfluencer. This connects with Scott’s concern about an “atmosphere of inauthenticity”, inspired in Oscar Wilde’s Dorian Gray, where Lord Henry shows the “influenced person as someone who no longer has a genuine identity” [cf. note 2]. For Max, it is very different to use technology to boost being “famous for being famous” than to use it to have a real impact on others. Tech enhances that impact.

Max has seen the world of international finance, European politics, Indian heavy industry and LatAm service markets in a very interesting biographical trip one can take with his stories. He decided to leave everything and move to Colombia, where he launched Realfluencers, now catering to the Latin American market. For him, instead of hiring a celebrity for zillions to arouse visibility, anyone can have short interactions with celebrities or non-celebrity experts to get some orientation or add value to something they’re doing. I like to think about his as a more decent perspective on influencer marketing, where the realfluencer actually has some credentials instead of noise. For Max, the idea is that it is not only the influencer who wins here, but the customer who actually gets something from the interaction (beyond a product’s visibility).

We’ve seen that influence is inevitable, but funneling it with some value might make more sense if we are conscious of our own vulnerability to content and emotions. It’s a drive for more authenticity, to to use L. Scott’s reasoning. And Max’s bet for a better influencer marketing world is one more of those stories of Unternehmergeist where people actually get something back. This takes us back to Cialdini and even Gabriel Tarde: it’s a matter of persuasion and imitation, yet we can be critical enough to choose persuasive people and content that bring some value, otherwise we’ll be subject to the almost inevitable mass influence and the dilution of our identity into some artificial patchwork. As the dynamics of the branding world continue to affect producers and customers alike, I still have some hope that real value-added is at the reach of normal people. Max’s quest is one of those few roads that can lead to the sweet spot of Rome.

Here’s a link to the Realfluencers platform in case you’re curious.

[1] Original story in Seneca. De Brevitate Vitae, 20.4.

[2] Scott, L. (2019, April 21). A history of the influencer, from Shakespeare to Instagram. The New Yorker. URL: https://www.newyorker.com/culture/annals-of-inquiry/a-history-of-the-influencer-from-shakespeare-to-instagram

[3] See for example Manhood, S.S., Levy, D., Vasan, R.S. & Wang, T.J. (2014). The Framingham Heart Study and the Epidemiology of Cardiovascular Diseases: A Historical Perspective. The Lancet, 383 (9921), 999-1008. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61752-3 Also interesting is Christaki’s TED talk in 2010:The hidden influence of social networks. URL: https://www.ted.com/talks/nicholas_christakis_the_hidden_influence_of_social_networks

[4] Kramer et al. (2014). Experimental Evidence of Massive-Scale Emotional Contagion through Social Networks. PNAS, 111 (24), 8788-8790. URL: https://www.pnas.org/doi/epdf/10.1073/pnas.1320040111

[5] Cialdini, R.B. (2005). What's the best device for engaging student interest? the answer is the title. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 24 (1), 22-29.

[6] Hoos, B. (2019). The psychology of influencer marketing. Forbes. URL: https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesagencycouncil/2019/08/22/the-psychology-of-influencer-marketing/?sh=2b1913f4e1be

Contact

behar@berlin-international.de

Address

Berlin, Bogotá, Monterrey or Madrid